Exploring Inuit Health Beyond the Individual: A Socio-Ecological Approach

- Caryl Joy Marbella

- Mar 6, 2022

- 6 min read

What is the Socio- Ecological Model?

The Socio-ecological Model (SEM) of health recognizes the dynamic interrelatedness between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Ecological frameworks help us understand how an individual interacts with their environment and such understanding is useful in developing effective multi-level approaches in helping to improve health behaviors (Sallis et al., 2008).

According to Sallis et al. (2008), the basic premise of this model is that providing individuals with the skills and motivation is not effective if the environments and policies are making it difficult for individuals to make healthy behaviours the easy choice. This model encourages health professionals to be creative and inclusive in generating evidence on factors and behavioural influences at multiple levels and translate into multilevel intervention for improved health outcomes. In relation to my work with the Inuvialuit in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Northwest Territories, I follow the SEM in understanding the several personal and environmental factors that could influence Inuit health behaviours.

Social Determinants of Inuit Health

Social determinants of health are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices” (World Health Organization, 2013). According to a report from the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), a national Inuit organization in Canada that represents the four Inuit regions, the following eleven factors have been articulated as the key social determinants of Inuit Health (ITK, 2017):

· quality of early childhood development;

· culture and language;

· livelihoods;

· income distribution;

· housing;

· personal safety and security;

· education;

· food security;

· availability of health services;

· mental wellness; and

· the environment.

It is important that SDH is considered at every level of the SEM framework. Doing such allows for a more holistic outlook on the overall health status of Inuit beyond just the individual. For the purpose of this submission, SEM will be used to understand obesity and other chronic diseases in Arctic Inuit populations in Canada.

Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic have been undergoing ‘nutritional transition’ which is characterized by a shift away from traditional eating and hunting patterns to a more westernized way of life which has been associated with increased obesity and other chronic diseases (Sharma, 2010). From the continued pressure to acculturate and adoption of Western values, the Inuit population is developing ‘energy balance-related’ health problems such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease (Akande et al., 2015). Such transition and its health outcomes in the Inuit population require looking at the influencing factors in a holistic lens beyond the individual to effectively operationalize multi-level interventions on Inuit health behaviours.

Energy Balance-related Health Problems in Inuit and the SEM Framework

As a consequence of social and cultural changes in the Canadian Arctic over the past several

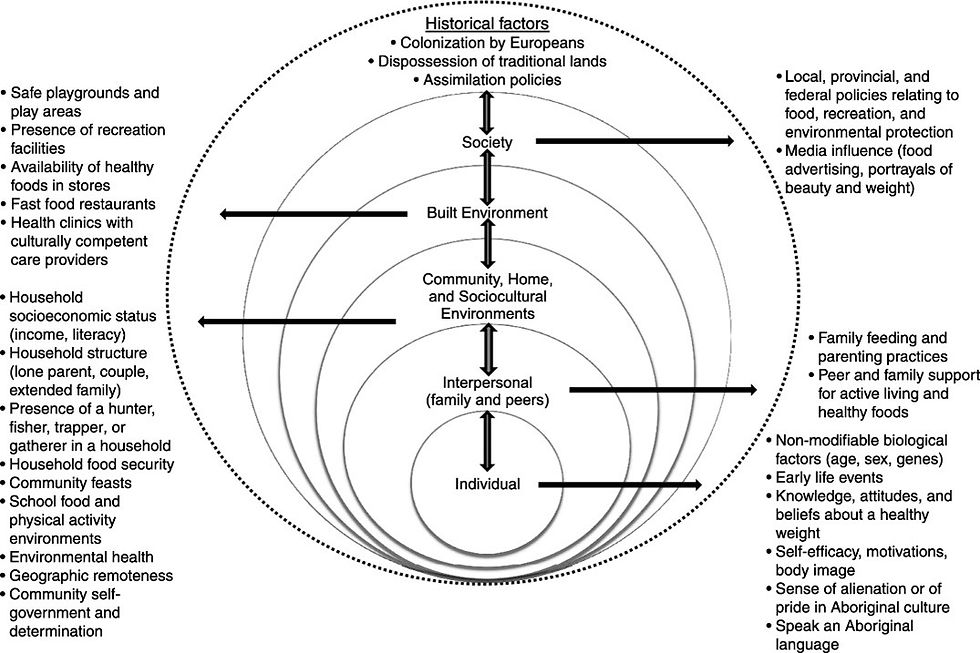

decades, there is an increased prevalence of energy balance-related health problems such as obesity (Akande et al., 2015; Hopping et al., 2010). To my knowledge, there has been no specific Inuit health SEM framework developed in the literature. For the purpose of this submission, I will be using the Ecological model for understanding obesity in Aboriginal children in Canada (Figure 1) and the Inuit community health research model (Figure 2), to guide me in exploring existing Inuit-specific multi-level health interventions.

At the individual level, provided in Figure 1, intrapersonal factors such as genetic predisposition, early childhood development, knowledge and attitudes, self-efficacy, body image, and relationship to culture and language (Willows et al., 2012). Historically, Inuit in Canada have a low prevalence of non-communicable diseases due to their highly physically active nomadic lifestyle and nutrient-dense diet (Hopping et al., 2010; Takano, 2005). According to Hopping et al. (2010), there is a co-existence of overweight or obesity and high levels of Physical Activity among the Inuit. We know that self-report measures are highly susceptible to social desirability bias, however, this shows that Inuit have their own preferred modes of physical activity that may be rooted in their own knowledge and attitudes towards physical activity and their culture. As a result of the legacy of residential schools and colonialism, there is an increasing prevalence of English language use combined with a decline in the use of Inuit language. According to ITK (2017), maintaining a sense of individual identity requires the preservation of language and cultural practices.

Family and peers are important interpersonal supports and are reflected in the SEM framework. Historically, most Inuit lived on the land with their extended family in small transient camps following wildlife and moving according to seasons (Sharma, 2010). Intergenerational trauma as a result of the residential school system led to language loss, assimilation, loss of parenting skills, and family upheavals (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2002). The feeling of sense of belonging allows people the feeling of being supported and a part of something larger than themselves, it also helps with problem-solving capabilities and managing life situations which are known to have a positive influence on long-term physical and mental health (ITK, 2017)

The National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working party in Australia, defines health as “not just the physical well-being of an individual but the social, emotional, and cultural well-being of the whole community” (Houston & Legge, 2010). In a study done using the 2001 Aboriginal Peoples Survey in Canada, which explored the dimensions of health for Canada’s Inuit, four health dimensions emerged from the Inuit sample which are (1) social support, (2) personal wellness, (3) physical function, and (4) community wellness (Richmond et al., 2007). The most profound finding in this study shows that Inuit conceptualizations of health and healing are shaped by the individual’s physical characteristics (e.g., chronic condition, disability, physical fitness, mental health) as well as characteristics of their families and community (e.g., social supports, social problems in the community, community wellness) (Richmond et al., 2007). Indeed, community health plays a huge role in the overall health and well-being of Inuit, and promoting physical health is multidimensional.

Finally, at the societal and environmental level, the rapid cultural and linguistic change in Inuit communities is attributed to colonialism, stigmatization, marginalization, and racism which have been known to cause detrimental effects on overall health (ITK, 2017). It was determined that the key action for future success in Inuit health is self-determination, in parallel with Inuit-specific and Inuit-led initiatives in all levels of the government (ITK, 2017). Furthermore, the physical and natural environment also plays a huge role in the quality of health of Inuit. When the Canadian government began to actively relocate Inuit to permanent communities with low-cost housing, medical facilities, and contemporary commerce, dramatic socio-cultural changes occurred which affected their overall well-being (ITK, 2017).

Healthy Foods North (HFN) is an intervention program specifically designed for Inuit and Inuvialuit to improve diet and physical activity (Sharma, 2010). It is a novel, multi-institutional, and culturally appropriate program that seeks to improve nutrition and reduce the risk of chronic disease (Sharma, 2010). This program recognizes that Inuit health is multidimensional and requires a broader understanding of societal factors. It functions at the individual, household, community, and institutional levels and is delivered throughout different communities (Sharma, 2010).

Within the SEM framework and the evidence provided from the literature that focused on Inuit health across different levels: individual, interpersonal, community, and societal, the common theme that emerged is holistic, coordinated, innovative, and Inuit-specific efforts in preventing chronic diseases and promoting overall health and wellness. The SEM framework informs health professionals of important Inuit ideologies and recognizes the multidimensional concepts of Inuit health beyond just the individual level attributes such as chronic disease or physical activity limitations.

References

Akande, V. O., Hendriks, A. M., Ruiter, R. A., & Kremers, S. P. (2015). Determinants of dietary behavior and physical activity among Canadian Inuit: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0252-y

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 18). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention |violence prevention|injury Center|CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html

A condensed timeline of events - first nations healing. (2002). Retrieved March 1, 2022, from http://firstnationshealing.com/resources/condensed-timeline-2.pdf

Hopping, B. N., Erber, E., Beck, L., De Roose, E., & Sharma, S. (2010). Inuvialuit adults in the Canadian Arctic have a high body mass index and self-reported physical activity. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277x.2010.01103.x

Hopping, B. N., Erber, E., Mead, E., Roache, C., & Sharma, S. (2010). High levels of physical activity and obesity co-exist amongst Inuit adults in Arctic Canada. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, 110–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277x.2010.01096.x

Houston, S., & Legge, D. (2010). Aboriginal health research and the National Aboriginal Health Strategy. Australian Journal of Public Health, 16(2), 114–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.1992.tb00037.x

Reupert, A. (2017). A socio-ecological framework for mental health and well-being. Advances in Mental Health, 15(2), 105–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2017.1342902

Richmond, C., Ross, N., & Bernier, J. (2007). Exploring Indigenous Concepts of Health: The Dimensions of Métis and Inuit Health. Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi). Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/115/?

utm_source=ir.lib.uwo.ca%2Faprci%2F115&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

Sallis, J., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. (2008). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, research and Practice. Jossey-Bass.

Sharma, S. (2010). Assessing diet and lifestyle in the Canadian Arctic inuit and Inuvialuit to inform a nutrition and Physical Activity Intervention Programme. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277x.2010.01093.x

Williams, O., & Swierad, E. (2019). A multisensory multilevel health education model for diverse communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(5), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050872

Willows, N. D., Hanley, A. J. G., & Delormier, T. (2012). A socioecological framework to understand weight-related issues in Aboriginal children in Canada. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-128

World Health Organization. (2013). Social Determinants of Health: Key Concepts. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 1, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/social-determinants-of-health-key-concepts

Comments