Coming Full Circle: Understanding Inuit Health and Wellness

- Caryl Joy Marbella

- Apr 5, 2022

- 7 min read

A Culmination of MHST 601 Learnings and Reflections

This blog post is a culmination of my learnings and reflections on Inuit Health and wellness in relation to the several course units we covered and explored in MHST 601. My gained experiences from collaborating with Northern communities and working for an Inuit land claim organization equipped me with the baseline knowledge to reflect on and tools to explore the existing strengths and barriers to improving Inuit health and wellness. In this post, I will be sharing some of my learnings and reflections on Inuit social determinants of health, multilevel health models, chronic disease management and prevention, as well as future directions in relation to remote Inuit communities.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices” (World Health Organization, 2013). Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) is the national Inuit organization in Canada, representing four Inuit regions – Nunatsiavut (Labrador), Nunavik (northern Quebec), Nunavut, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories. In ITK’s (2017) report on Social Determinants of Inuit Health, they emphasized eleven key determinants of Inuit health such as early childhood development, culture and language, livelihood, income distribution, housing, personal safety, education, food security, availability of health services, mental health and wellness, and the environment. As reported in the literature, Inuit continue to experience comparatively lower life expectancies, higher infant mortality, and suicide rates of any population group in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2015; ITK, 2017).

During this week in our course, everyone has shared relevant social determinants of health in Canada, and it can be observed that there is indeed a disparity in available supports and resources to address the mentioned factors between Indigenous communities especially remote communities, and the general Canadian population. It remains still in my observation from living up north and communicating with local community members, that there is still more work to do. According to ITK (2017), instilling Inuit self-determination empowers communities to have control over their own resources and identify services that match their needs. Through the forums and content curation on this topic, I was able to reflect on my understanding of the determinants and how they would affect the way we approach health promotion in remote Inuit communities.

Chronic Disease Management and Prevention

In connection to the identified social determinants of Inuit health, lifestyle-related chronic diseases are one of the health outcomes brought by health disparities in Indigenous populations. Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic have been undergoing ‘nutritional transition’ which is characterized by a shift away from traditional eating and hunting patterns to a more westernized way of life which has been associated with increased obesity and other chronic diseases (Sharma, 2010). Historically, Inuit in Canada have a low prevalence of non-communicable diseases due to their highly physically active nomadic lifestyle and nutrient-dense diet (Hopping et al., 2010; Takano, 2005). Furthermore, the physical and natural environment also plays a huge role in the quality of health of Inuit. When the Canadian government began to actively relocate Inuit to permanent communities with low-cost housing, medical facilities, and contemporary commerce, dramatic socio-cultural changes occurred which affected their overall well-being (ITK, 2017).

All the evidence provided from the literature and as identified by Inuit organizations and beneficiaries, show that chronic disease management should be approached in a coordinated, innovative, culturally appropriate, and holistic manner beyond just the individual (ITK, 2017). Throughout discussing this unit with my peers, I am able to expand my understanding of how different provinces in Canada approach chronic disease prevention and management. Canada as a diverse country should not be subjected to a one-size-fits-all approach to health care and prevention. I learned that in Indigenous populations, it is important that the healthcare model is grounded on historical and cultural context and priorities have to be identified by Indigenous peoples for Indigenous peoples.

Multilevel Models of Health

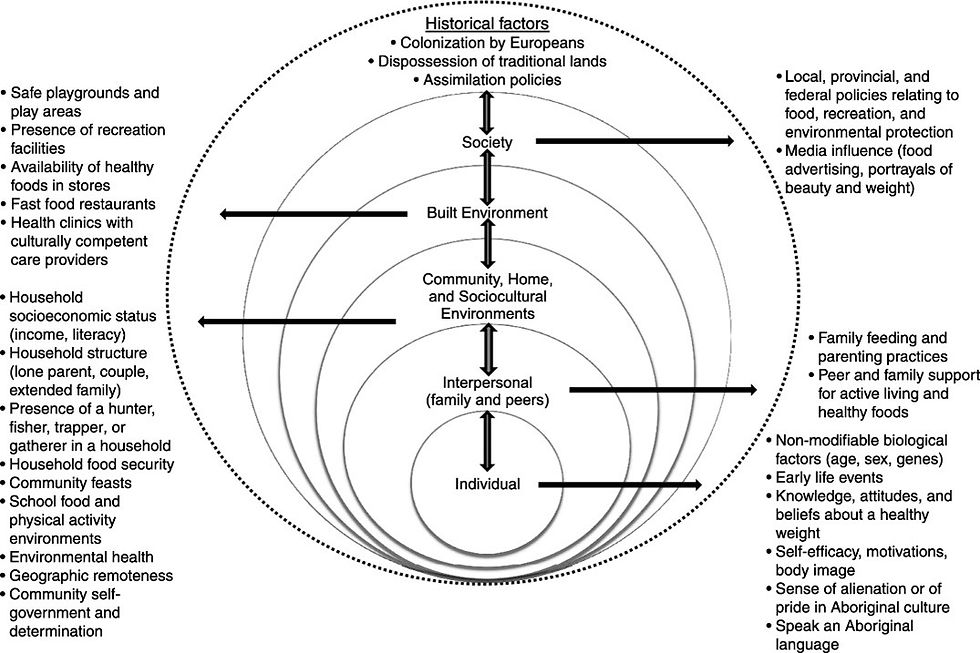

The Socio-ecological Model (SEM) of health recognizes the dynamic interrelatedness between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Ecological frameworks help us understand how an individual interacts with their environment and such understanding is useful in developing effective multi-level approaches in helping to improve health behaviors (Sallis et al., 2008). Living in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories and working for an Inuit Land claim organization, I found the following resources curated on my website to be useful in understanding the current health models implemented to address Inuit health determinants. It is evident that the Socio-ecological model (SEM) is being utilized in a lot of health promotion and intervention efforts concerning Indigenous health (Delafield et al., 2016; Gillies et al., 2020; Stotz et al., 2021). There is more of an emphasis on increased ownership and control of health programs and services and cultural competency for improved health outcomes. When this approach is applied to Indigenous health issues, it takes into account a variety of specific factors that influence their health results. This model incorporates the multiple levels that influence Aboriginal health, starting with individual variables and expanding outward to encompass interpersonal, community, environment, society, and historical influences.

A practical example of applying SEM in Inuit health projects is the current project our team is working on for an Inuit-land claim organization in the Northwest Territories. Our work focuses on identifying the existing strengths of Inuit health and building upon them as well as addressing the systemic gaps as identified by the Inuit themselves. The aim of this project is to collect Inuit-determined data on Inuit health and wellness to inform policies, programming, and health and wellness initiatives in the region. Inuk individuals are able to identify through the project their own personal needs and share their voice on behalf of their community. The project understands that consulting from a multi-level approach (individual, community, government, societal/historical, and environment) is important to achieve a holistic approach.

Future Directions

The Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada will play an important role in the future of Indigenous healthcare in Canada. The twenty-four health-related Calls to Action provide a framework for the health sector to initiate collaboration moving forward (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). To date, Indigenous peoples continue to be on the receiving end of health inequities and disparities due to ongoing colonization and unfit policies and legislation (Browne et al., 2016; Kyoon-Achan et al., 2019). A lack of attention to these influences leads to health inequities in Indigenous peoples and is reflected in the increased rates of illness and disease, food insecurity, living standards, and mental health (Browne et al., 2016; Eni et al., 2021; Lauziere et al., 2021). A true collaboration as led and identified by Indigenous groups in a post-colonial lens would truly reflect the priorities that needs to be addressed such as structural disadvantages that affect access, conditions, and the overall health of Indigenous peoples (Browne, 2012).

Conclusion

Overall, MHST 601 has been a platform for me and my peers to share our knowledge and continue to hone our passion for health and wellness. We had the opportunity to discover our own professional identities, check our biases and knowledge gaps, and overall explore the strengths and limitations of the health care system in Canada. I believe that through this course, I learned more about my profession and what I want to improve on as a researcher and as a health promoter. Indeed, productive conversations with peers and many opportunities to write about and reflect on different health-related topics had been beneficial in my understanding of the Canadian health care systems and my overall approach as a health researcher and promoter.

References

Browne, A. J., Varcoe, C., Lavoie, J., Smye, V., Wong, S. T., & Krause, M. & Fridkin, A. (2016). Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 544.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 18). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention |violence prevention| injury Center| CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html

Delafield, R., Hermosura, A. N., Ing, C. T., Hughes, C. K., Palakiko, D. M., Dillard, A., ... & Kaholokula, J. K. A. (2016). A community-based participatory research guided model for dissemination of evidence-based interventions. Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action, 10(4), 585.

Eni, R., Phillips-Beck, W., Achan, G. K., Lavoie, J. G., Kinew, K. A., & Katz, A. (2021). Decolonizing health in Canada: A Manitoba first nation perspective. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1-12.

Gillies, C., Blanchet, R., Gokiert, R., Farmer, A., Thorlakson, J., Hamonic, L., & Willows, N. D. (2020). School-based nutrition interventions for Indigenous children in Canada: A scoping review. BMC public health, 20(1), 1-12.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2017, March 24). Comprehensive report on the social determinants of Inuit health. Retrieved February 2022, from https://www.itk.ca/social-determinants-comprehensive-report/

Kyoon-Achan, G., Lavoie, J., Phillips-Beck, W., Kinew, K. A., Ibrahim, N., Sinclair, S., & Katz, A. (2019). What changes would Manitoba First Nations like to see in the primary healthcare they receive? A qualitative investigation. Healthcare Policy, 15(2), 85.

Lauzière, J., Fletcher, C., & Gaboury, I. (2021). Factors influencing the provision of care for Inuit in a mainstream residential addiction rehabilitation centre in Southern Canada, an instrumental case study into cultural safety. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 16(1), 1-15.

Sharma, S. (2010). Assessing diet and lifestyle in the Canadian Arctic inuit and Inuvialuit to inform a nutrition and Physical Activity Intervention Programme. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277x.2010.01093.x

Statistics Canada. (2015). Prevalence of diagnosed chronic conditions, by Aboriginal identity group, off-reserve population aged 20 or older, Canada, 2006/2007. Retrieved from

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

World Health Organization. (2013). Social Determinants of Health: Key Concepts. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 1, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/social-determinants-of-health-key-concepts

Comments